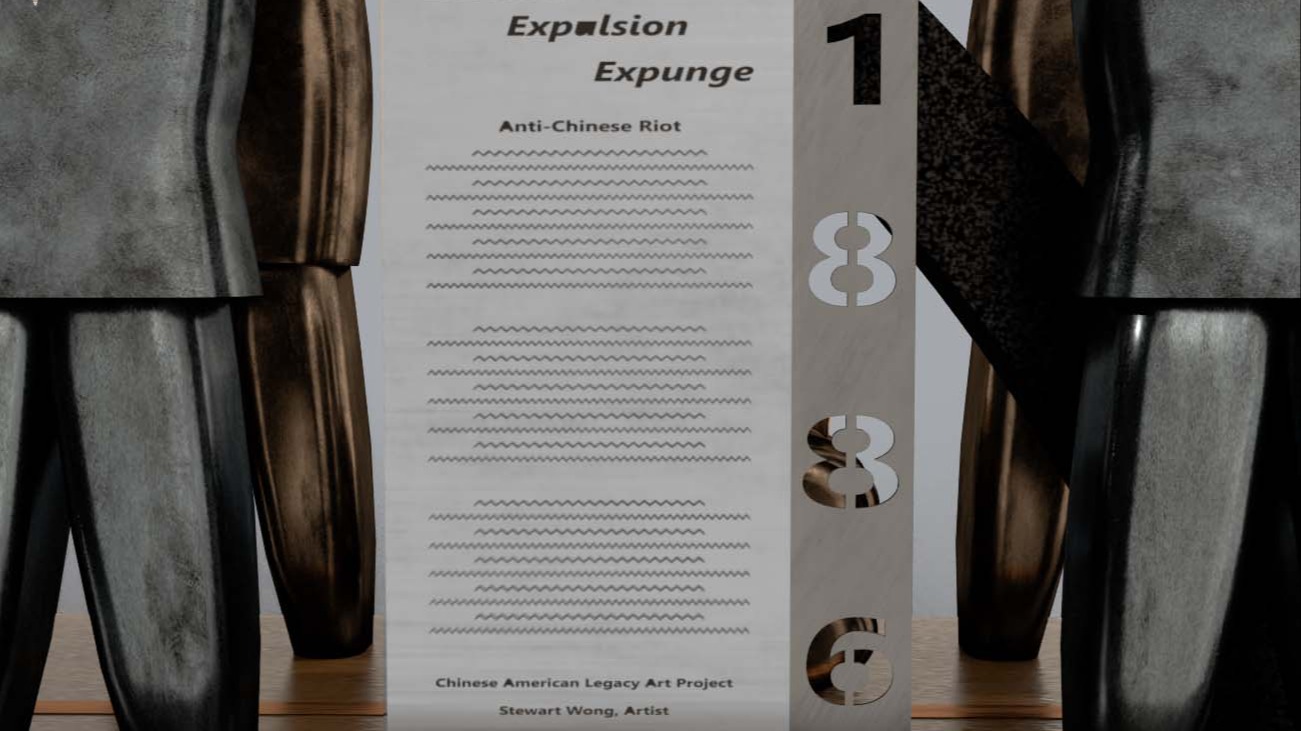

Chinese American Legacy Artwork Project

The Chinese American Legacy Artwork Project centers on the Feb.7, 1886 anti-Chinese riot in Seattle, one of the most horrific episodes in the city’s history. On that day, an angry mob invaded Chinatown and hauled all the Chinese to the waterfront to be sent away.

The riot was a manifestation of the anti-Chinese movement, a hate-driven crusade to remove the Chinese - whom many viewed as unfair labor competition, deceitful, filthy, inferior, and unassimilable – from the U.S. The movement began shortly after the arrival of the Chinese to America in the 1850s and lasted well pass the passage of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which prohibited Chinese laborers from immigrating to the U.S. and denied Chinese to become naturalized citizens.

The anti-Chinese sentiment towards the Chinese in Washington began even though there were very few of them there. After Washington became a territory in 1853, it passed a law denying Chinese the right to vote. Some 10 years later, it passed a law prohibiting Chinese to testify in courts in which a white person was a party, and “An Act to Protect Free White Labor Against Competition with Chinese Coolie Labor and to Discourage the Immigration of Chinese in the Territory,” which resulted in a poll tax levied on every Chinese.

But just as troublesome for the Chinese than the laws that were passed against them was the daily harassment, violence, and abuse they faced during the anti-Chinese era.

In the mid-1880s the economy became depressed which left many, including the Chinese, out of work. With white citizens already frustrated over the failure of the Chinese Exclusion Act to expel them, the anti-Chinese movement hit its climax. The prevailing view was that there would be jobs for whites if the Chinese were removed.

The spark that precipitated the anti-Chinese riot in Seattle was a revolt on September 2, 1885, at Rock Springs, Wyoming. There, 28 Chinese were murdered and over 500 were driven out of town. Three days later, a group of whites and Indians armed with rifles ambushed a camp of 35 Chinese while they slept at a hop farm in Squak Valley (now Issaquah). Three Chinese were injured and three killed. Five whites and two Indians were indicted, but they were acquitted after an eight-day trial.

Six days later, near the Coal Creek Mine in Newcastle, masked white men set fire to a building where Chinese workers resided. The building was destroyed, and 41 Chinese were driven from the area. Not too far away, at the Franklin Mines, another group of Chinese were expelled, and their quarters burnt down.

On November 3, the citizens of Tacoma loaded 700 Chinese onto wagons and hauled them out to trains headed for Portland. Two days later, the citizens returned to burn down the Chinese quarters. The Tacoma incident heightened tensions in Seattle and bolstered the anti-Chinese group’s belief that direct action was the best strategy for removing the Chinese.

Frightened by the events in Tacoma and the hostile atmosphere in Seattle, 150 Chinese left by boat and train over the next three days. Meanwhile, the situation in Seattle remained explosive. Indeed, on November 8,1885, the U.S. Secretary of War ordered federal troops to Seattle. The next day, 350 soldiers from Fort Vancouver arrived in Seattle with Governor Squire.

While the overwhelming majority of Seattle citizens wanted the Chinese out of the city, two groups emerged with differing ideas on how to get rid of them. One group, known as the “anti-Chinese” faction, wanted to take direct action by forcefully removing the Chinese. This group was led by the Knights of Labor. The other group was the “law and order” faction, which was made up of prominent citizens and city officials. They wanted the Chinese removed legally through legislative action.

Over the next two months, people waited for legislative action to remove the Chinese.

On December 3, 1885, the Seattle City Council passed the so-called “Cubic Air Ordinance,” which provided that each resident was entitled to a sleeping compartment 8’ x 8’ x 8’ and aimed at the Chinese, who were known to live in very congested housing units.

On February 5, 1886, the Seattle City Council passed additional ordinances to expedite the removal of Chinese from the city. One prohibited the operation of wash houses in wooden buildings. Another prohibited the sale of goods in the streets. Still another instituted a license fee for itinerant and non-residential fruit vendors.

Clearly frustrated with the presence of Chinese in the city, the anti-Chinese faction took direct action to remove them. On Sunday, February 7, 1886, a vicious mob of 1,500 invaded the Chinese quarters forcing some 350 Chinese onto wagons and hauled to the dock to be shipped away. The departure was delayed one day by a writ of habeas corpus, sworn by a Chinese merchant who alleged that his countrymen were unlawfully detained abroad the ship. On February 8, the ship left Seattle with 196 Chinese. Two shiploads later, most of the Chinese were driven out of the city, and the anti-Chinese forces essentially achieved its goal of driving out the Chinese from Seattle.

Present Day

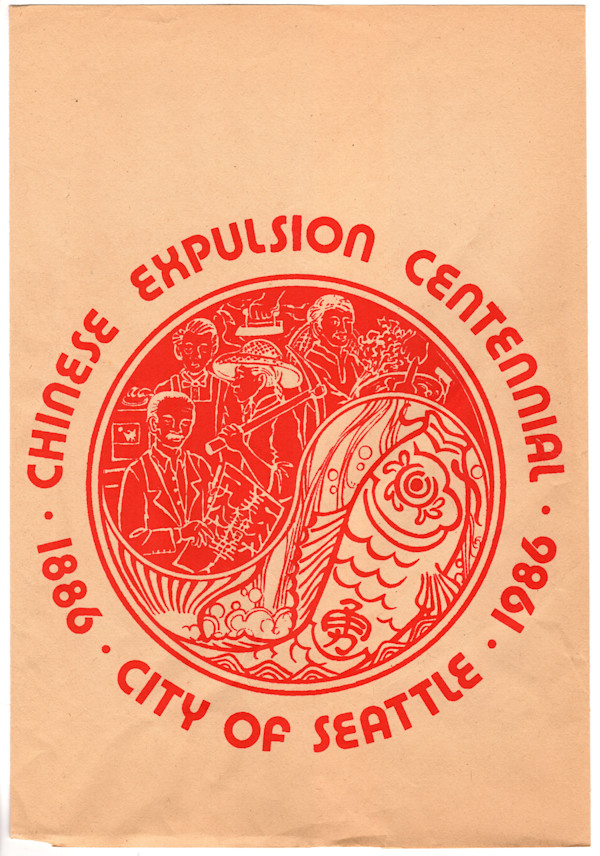

The need and desire for the Chinese American Legacy Artwork Project cannot be overstated. For five decades the Seattle Chinese community and others has drawn attention to the significance and meaning of the 1886 riot through rallies, marches, literature, and forums. In the past 10 years, a community-based committee has continually worked to design, fabricate, and install this artwork. The artwork reveals a legacy that must be told - to understand the present, it is necessary to know and understand the past. Indeed, the artwork represents an important episode in Seattle’s history pertaining to exclusionary immigration, race and ethnic relations, diversity, and racial hate. For sure, the artwork underscores, reinforces, and augments the current anti-Asian hate as well as the broader anti -race, -ethnic, and -religious hate campaigns. Moreover, the artwork supplements the demand for Asian American studies and ethnic studies curriculum in the schools. For Chinese it brings about a sense of belonging, pride, and recognition, as they learn of the trauma and struggle their earlier immigrants had to endure and overcome. The City of Seattle passed a resolution in 2015 expressing regret for the 1886 anti-Chinese riot, while acknowledging the contributions of the Chinese to Seattle, and reaffirming the city’s commitment to the civil rights of all people. This artwork augments and amplifies that resolution

Donate

Acknowledgements