Foodways of the Early Chinese

When you hear the two words Chinese and American together, popular dishes such as Chop Suey, General Tso's Chicken, or egg rolls may initially pop up in one’s mind. There is no doubt that Chinese American cuisine holds a significant role in American culture. Food has held a central place in the lives of the Chinese in America that not only encompasses what we are served at restaurants but also the complex and profound ways food has helped early Chinese sojourners, their descendants, and more recent Chinese immigrants survive in the United States.

For the Chinese in the United States, the relationship between food and labor continues to shape the lives of individuals, families, and communities. Food holds an essential role in building community, bringing comfort, and providing a means of survival. Since the arrival of the first Chinese sojourners and immigrants to the Americas in the 1800s, the few job opportunities available to them in domestic labor and importation markets provided them profit through food. Whether it be as cooks, gardeners, fishermen, labor contractors, or as railroad workers – the foodways of the early Chinese in the U.S. defined their survival through the expulsions, demonstrated their ingenuity, and shaped their lifestyle in Washington.

You are a young 15-year-old boy from southern China in the mid-19th century. Like countless other countrymen, famine, an unstable economy, and political unrest in your homelands has pushed you all to search for more prospects in the United States to provide for your families. Wasting no time, you find yourself the smallest out of a group of 1,800 migrants on a ship headed San Francisco. Upon arrival, You soon make your way up north to Seattle to stay with your cousin, Chun Chin Hock of the Wa Chong Company and reside at his store until you find work and eventually open your own successful cigar manufacturing company that provides other Chinese jobs. Yet, the constant anti-Chinese sentiment that has threatened you since reaching the United States has exploded. The Knights of Labor begin to violently run the Chinese out of Seattle and Tacoma. These riots wreck your company and your workers’ livelihoods. Despite this bitter period, your perseverance, adaptability, and support from the community, helps you survive the anti-Chinese expulsions and the Great Seattle Fire. By 1873, the Chinese population has increased since the riots and your cousin, Chun Chin Hock, makes you a junior partner at Wa Chong Company. This opens your doors into the dry goods importing business. Eventually you become one of the wealthiest Chinese in the Pacific Northwest who helped spearhead bringing Washington made flour to Chinese markets for the first time. You then explore shipping herring from Washington to China and maintain the success of Wa Chong Company’s firework importation business.

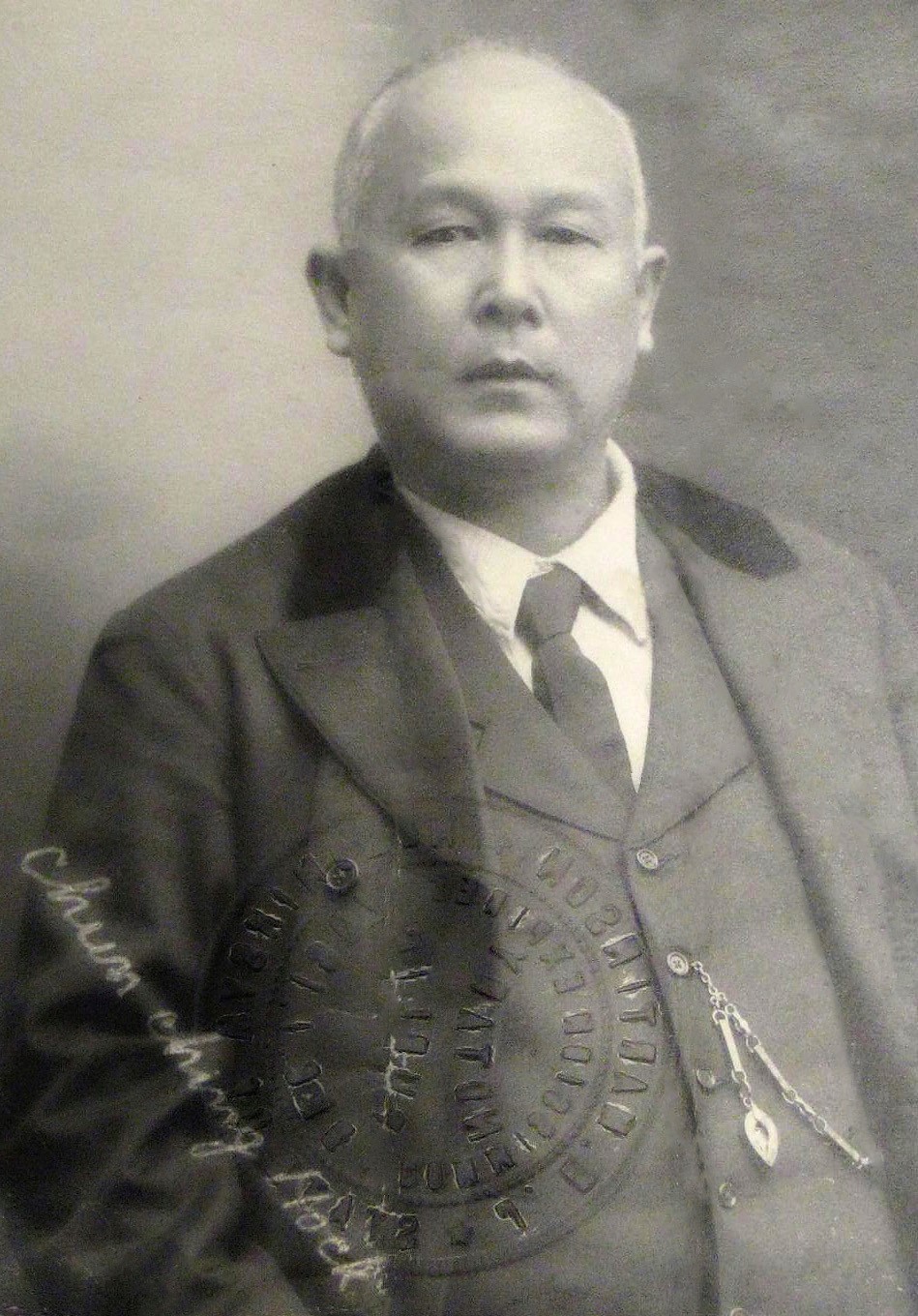

This is just a glance into the life of Mr. Woo Gen – a partner at the Wa Chong Company and one of the earliest Chinese settlers of Seattle at the time of his interview with C.H. Burnett in 1924. His story gives insight into the effects of the anti-Chinese expulsion in Washington, the reliance many had on Chinese labor contractors, as well as how the presence of the dry goods the merchant and importation business had in the success and survival of Chinese sojourners.

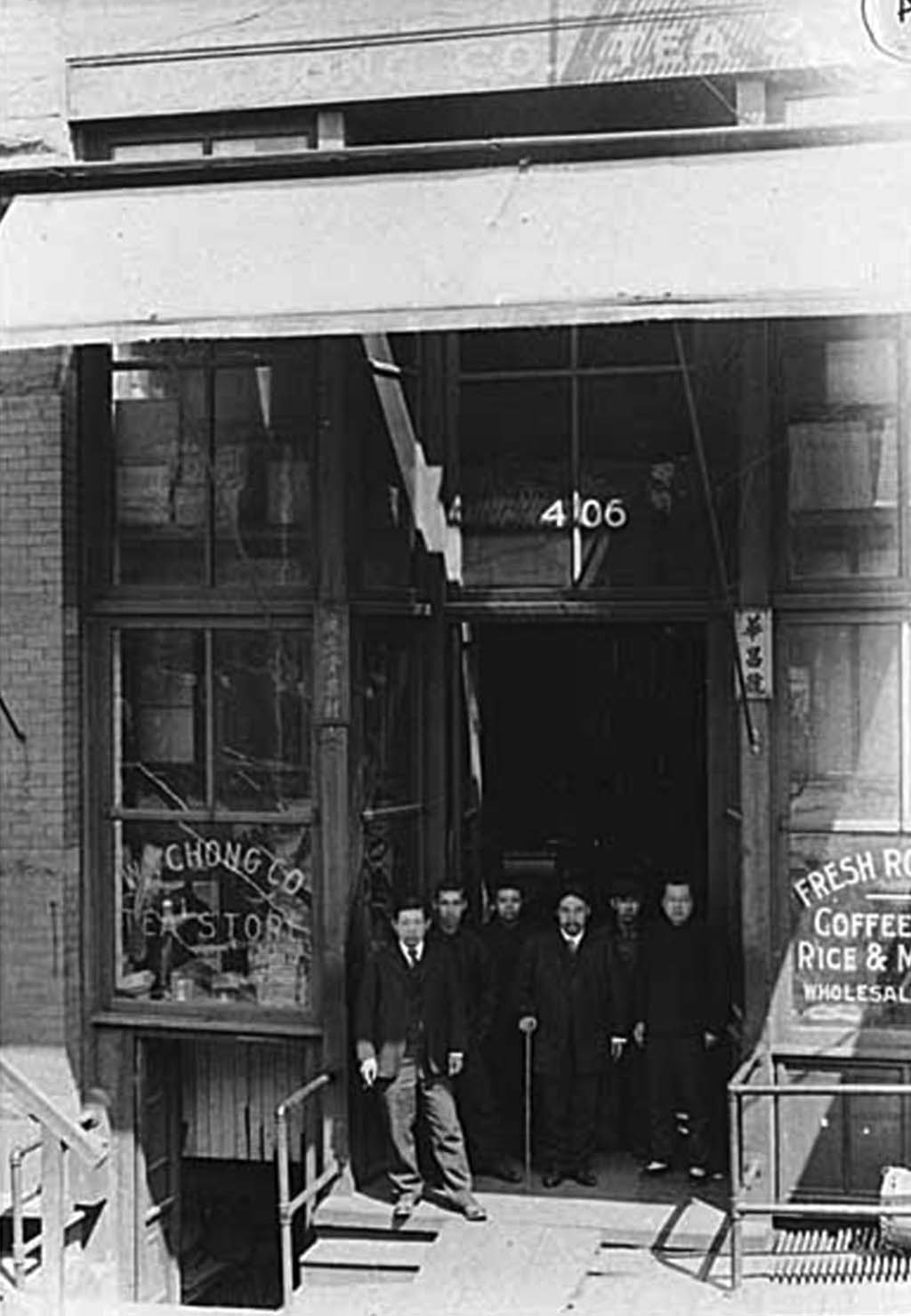

he Wa Chong building was located at 406 S. Main Street, in Seattle's old Chinatown. The store carried Chinese and Japanese merchandise and was the largest Chinese business of its time in Seattle. The man on the left is Woo Gen, and the man in the center (with cane) is Chin Chun Hock. Circa 1905. Wing Luke Museum Photograph Collection

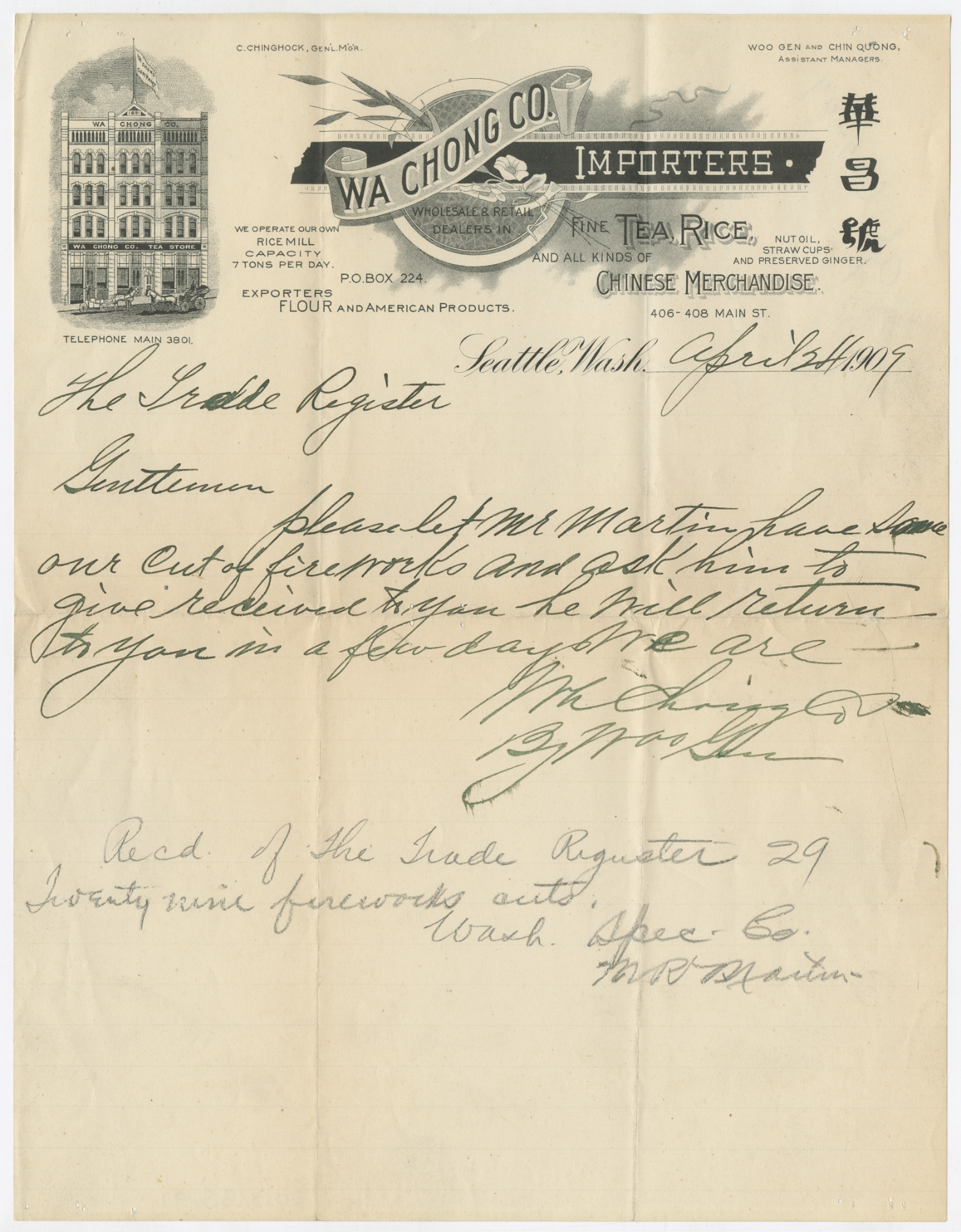

Handwritten on letterhead: ‘Seattle Trade Register // Gentlemen, Please let Mr. Martin have our cut of fireworks and ask him to give received to you, he will return to you in a few days. // We are Wa Chong Co., By Woo Gen’ - courtesy of Museum of History & Industry, Seattle.

The Foodways of Chinese Laborers

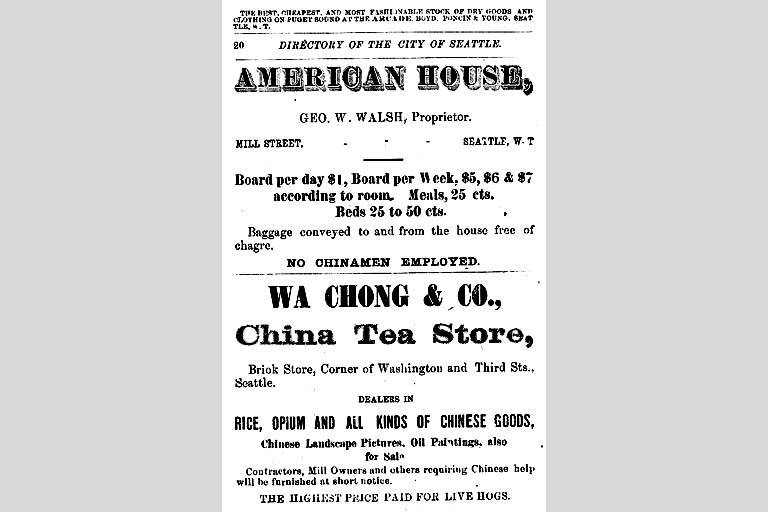

One of the oldest and most well-known Chinese general merchandise stores during the late 19th century, was the Wa Chong Company founded in 1868 by Chun Ching Hock, who was thought to be the first Chinese immigrant in Seattle (Riddle, 2014). Wa Chong Company had its humble beginnings in selling dry goods such as tea, flour, rice, coffee and even fireworks (Riddle, 2014). The enterprise was later managed by Mr. Woo Gen who continued to bring profit to the corporation through mass importation of flour and salt herring to China.

National Archives, RG 85, Chinese Exclusion Case Act Files (Seattle) SE-5872, NAID 298951, Box 47, Case Number 31695, Chun Ching Hock.

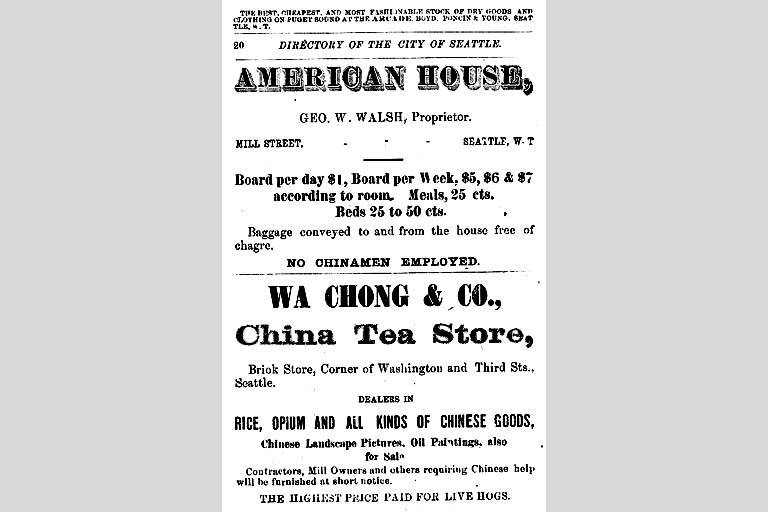

Advertisements from the Seattle City Directory of 1879 for American House and Wa Chong and Co. Courtesy of University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, SOC0003

The prevalence of food in the success of labor contracting companies such as Wa Chong Company can be seen in the types of dry goods they imported. In Seattle, these merchandise stores also sold to white, Indigenous, other immigrant clientele, as well as other ethnic Chinese people. Most of which went to work in canneries, hop farms, the Northern Pacific Railroad Line, and as domestic servants. Contracting companies like Wa Chong Company also had “exclusive rights to supply food and supplies for the laborers” (Chin, 1977). For these laborers, their desire for familiar foods and traditional foraging practices not only influenced their diets, but also the environment of the Pacific Northwest.

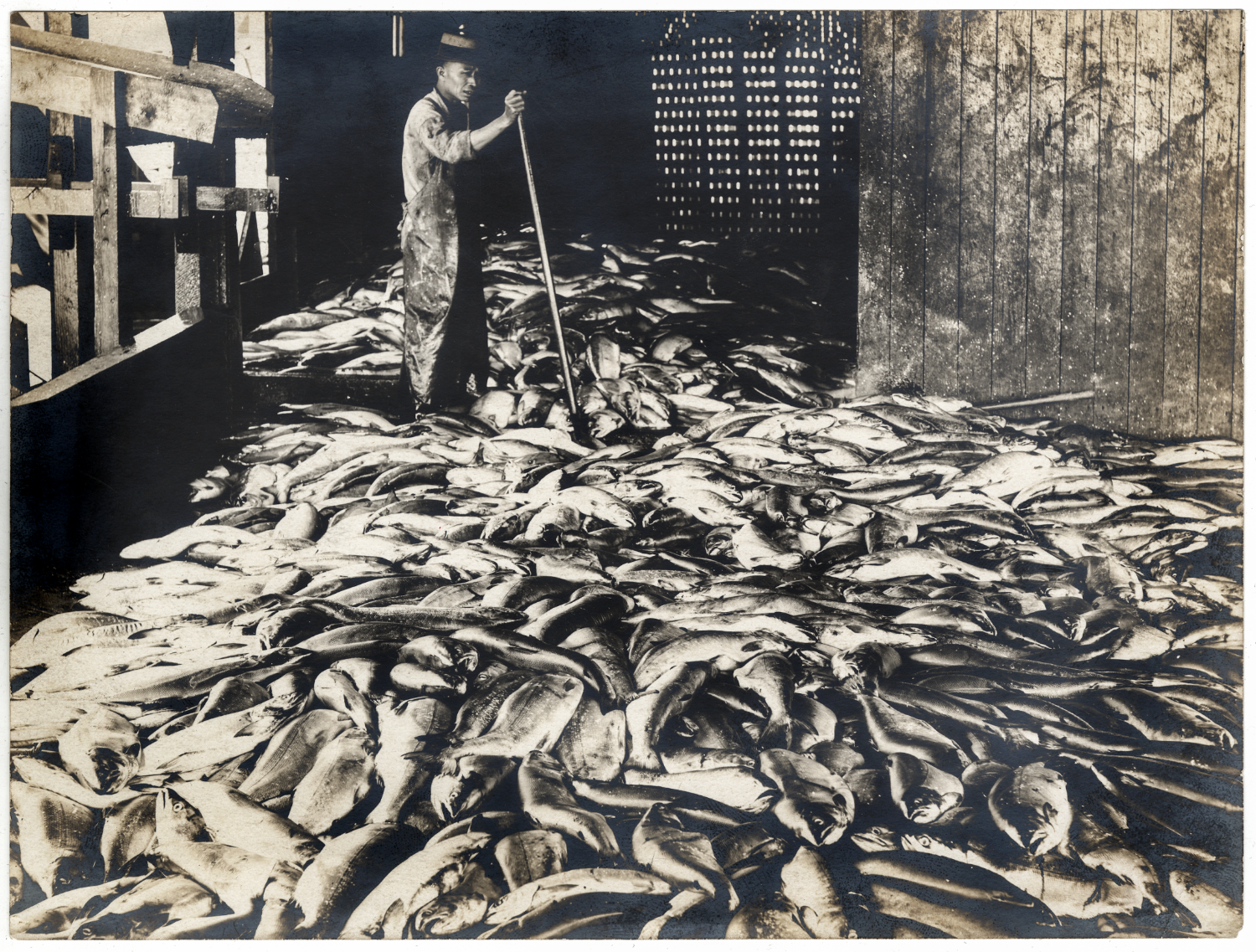

One such group were fishermen and contracted cannery workers. In the Elliott Bay, the Chinese fished extensively with purse seines which they were the first to introduce in the area. “The Chinese were so efficient with their nets that some Native Americans complained about depletion of the fish population” (Liestman, 1998). Through the use of their own traditional fishing techniques as well as learned methods from Indigenous groups, the Chinese found profit in the fishing industry. There were many Chinese who resided along the Puget Sound area who developed their own isolated fishing settlements where they caught, dried, and sold their catches. One such village “was known locally as Hong Kong” and was located “on the west end of Maury Island, near Manzanita (Liestman, 1998). On the Columbia Gorge, Chinese cannery workers were known to supplement their diets by fishing in streams, and gathering mussels and seaweed.

Chinese worker in Seattle cannery with fish - courtesy of Museum of History & Industry, Seattle.

A significant number of Chinese also laid down railroad tracks in Washington. About “two thousand Chinese were hired to work on the Northern Pacific Railroad line from Kalama…to Tacoma” (The Tacoma Chinese Reconciliation Project Foundation). Many of whom were contracted out by the Wa Chong Company Unlike white railway workers, the Chinese were not provided free meals or board by railway companies. While this discriminatory treatment placed more financial hardship on the Chinese, it simultaneously allowed the laborers to take more control of what went into their diets. Compared to the white railmen, the Chinese incorporated a lot more vegetables and protein into their meals. Pork was “the principle meat” they “consumed in the Pacific Northwest” as hogs were easy to raise (Liestman 18). Imported food such as teas and rice were brought from China by the local Chinese merchant companies who shipped these goods to labor camps and small Chinatowns along the railroad for laborers to buy. The Chinese also scavenged for herbs, fruits, sea food, and other plants that helped supplement their stews and stir frys. The practice of boiling water for tea played a large role in keeping the Chinese healthy from waterborne illnesses that many white workers suffered from (Stimpson). However, the unique ways in which the Chinese prepared their food compared to other non Chinese Washington residents only added to the resentment many had against them as economic conditions worsened. Racist sentiments attached to the food practices of the Chinese helped fuel the violent expulsion of them from the Puget Sound area and other Washington settlements. Their resourcefulness and ability to “‘live on practically nothing’” furthered the propaganda that the Chinese were no better than pests who took jobs and didn’t add to the local economy as many sent most of their money back home to their families (The Tacoma Chinese Reconciliation Park).

a group of Chinese coolies on the switchback near the summit of the Cascades, in 1886. Possibly on the tracks of the Northern Pacific Railroad - courtesy of UW Libraries Special Collections

Chinese Railway workers on the Columbia Gorge - courtesy of University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, SOC0048

Today we still see similar discriminatory practices and racist beliefs held against Chinese food and other ethnic cuisines in the United States. Oftentimes the food is described as too greasy, unsanitary, or as exaggerated stereotypes. It is these same types of dangerous ideologies that were used to justify the 1880s expulsions and riots against the Chinese in Washington. However, the food practices of the early Chinese in Seattle and the North Pacific West demonstrates the adaptability of these sojourners in a hostile new environment. Faced with racial persecution and unfamiliar terrain, the Chinese were able to not only adopt new foodways but also preserve their own traditional culinary practices which in turn preserved their health and helped them establish themselves in a new country.

Maeson is a Chinese American woman who finds passion in learning, educating, and exploring the histories of Asians peoples in the U.S.

Terrell, Ellen. “A Seattle Tea Merchant in Chinatown: Inside Adams.” The Library of Congress, 9 May 2023, blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2023/05/seattle-tea-merchant-chinatown/.

Riddle, Margaret. “Chun Ching Hock Opens the WA Chong Company in Seattle on December 15,.” Chun Ching Hock Opens the Wa Chong Company in Seattle on December 15, 1868., www.historylink.org/File/10800. Accessed 29 Mar. 2024.

Liestman, Daniel. “Nineteenth-Century Chinese and the Environment of the Pacific Northwest.” The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, vol. 90, no. 1, 1998, pp. 17–29. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40492442. Accessed 29 Mar. 2024.

The Life History of Mr. Woo Gen Interviewed by C. H. Burnett, July 29th, 1924

Chin, Doug. “Reevaluating History - The Real Role of the Chinese Merchant Elite.” The International Examiner, Oct. 1977, pp. 4–5.

“Expulsion: The Tacoma Method.” Tacoma Chinese Reconciliation Park, 28 Nov. 2013, tacomachinesepark.org/tacoma-chinese-park/expulsion-the-tacoma-method/.

Chinese Immigrants, Washington State History Museum, www.washingtonhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/chineseImmigrants-1.pdf. Accessed 22 Apr. 2024.

Parks, Shoshi. “Inside the Diet That Fueled Chinese Transcontinental Railroad Workers.” Atlas Obscura, Atlas Obscura, 7 Dec. 2022, www.atlasobscura.com/articles/diets-transcontinental-railroad.

“Collections and Research - Mohai.” Collections and Research -, mohai.org/collections-and-research/#order-photos. Accessed 22 Apr. 2024.

::: University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections :::, content.lib.washington.edu/. Accessed 22 Apr. 2024.

“Online Collection and Exhibits.” Wing Luke Collections, collections.wingluke.org/. Accessed 22 Apr. 2024.