Seattle’s First Yellow Peril

Almost 140 years ago, Seattle’s Chinese population was almost completely forcibly expelled. During 1885-1886 there were two forces competing against each other; not on whether to keep or remove the Chinese, but on how to best remove the Chinese from Seattle. Although racial tension between white Americans and Chinese workers was always present it escalated in the 80s; the United States was heading into a recession causing widespread unemployment and the Chinese were a convenient target to blame for the declining economic situations. The first and larger of the two groups were the sinophobes or the “anti-Chinese”. They were composed of working class men and led by the Knights of Labor. The Knights of Labor were a major labor organization and also primarily responsible for the expulsion of the Chinese population in Tacoma only a year prior. Their violent but successful approach on expelling out the Chinese became known as the Tacoma method and it would also be successfully executed in Anacortes and Port Townsend. Labor organizations and white laborers in particular had a growing hate for Chinese works as they were used as an alternative to relatively more expensive white labor. The other of the two groups were the “law and order” group. Made up of city officials and other prominent figures, the law and order group sought to remove the Chinese by way of the law. By this time the federal government had already passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 which prohibited Chinese laborers from coming into the United States. Although their violence was tempered their racist and xenophobic intent was the same as the sinophobes.

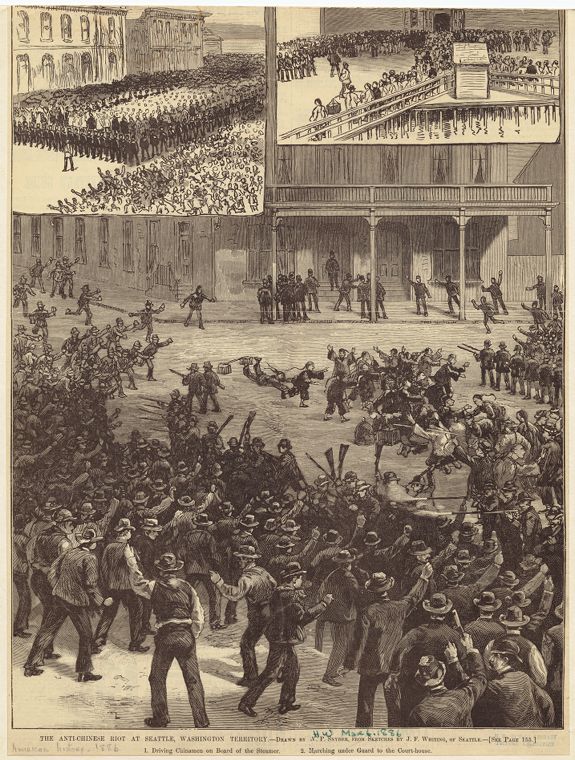

Drawn by W.P. Snyder, from sketches by J.F. Whiting. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. (1886). The anti-Chinese riot at Seattle, Washington Territory Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/35bc4780-c533-012f-8f11-58d385a7bc34

Demonstrating the widespread anti-Chinese sentiment in Seattle, on October 24th, 1885, 2,500 people partook in an anti-Chinese demonstration led by the anti-Chinese faction. At this time there were only about 400 Chinese in Seattle. On November 4, both the law and order and anti-Chinese factor decided to meet with the Chinese labor leaders. The meeting ended with an agreement for the Chinese to leave Seattle. Though in reality, Chinese leaders likely knew the two groups would stop at nothing to remove them and had little actual choice in them staying or not. Four days later, on November 8, a day after the Chinese in Tacoma were removed, the U.S. Secretary of War ordered federal troops to Seattle. These troops both protected and harassed the Chinese in Seattle. Four men were beaten and one was thrown into the bay. In addition, some soldiers visited the Chinese quarters to collect a tax from each of them, collecting about $150 total. The troops' stay arguably caused more harm and was ineffective in significantly staving off the violence and they returned to Fort Vancouver on November 17th. There was a stalemate for two months afterward as the anti-Chinese faction was being unseriously and unsuccessfully prosecuted by the law and order members.

With tensions at a peak from the lack of action by the law and order faction, the Chinese quarters were stormed by members of the anti-Chinese group on February the 7th, 1886. Most of the remaining 350 Chinese were dragged onto wagons and taken to the dock to be sent away on the steamer “Queen of the Pacific.” The police came to ensure the Chinese were not abused in any way by the mob at the dock. Mayor Yesler appealed to Governor Squires, who was in Seattle by chance, to take action. The governor did not declare martial law and simply declared a proclamation warning people of breaking the law and urging the mob to return to their homes. The protection of the Chinese was obviously not so significant to him. Meanwhile, Captain John Alexander of the Queen Pacific agreed with the anti-Chinese leaders to take the Chinese for $7 a person. The group raised $600 and paid the fair of 89 Chinese with another nine paying the fair themselves. Their departure would be delayed by a day due to a writ of habeas corpus. Sixteen of the 97 decided to stay in Seattle after reassurance by Judge Greene. Afterwards, 196 Chinese boarded, reaching the ship’s capacity limit, and left Seattle. The remaining Chinese were escorted back when violence erupted between the mob and guards. This incident provoked the governor to declare martial law. Although at first denied, President Cleveland relented and on February 10th troops arrived. Four days later, 110 more Chinese boarded leaving only a fraction left in Seattle. The few Chinese left in Seattle sustained the Chinatown for the next 140 years despite sustained strong racial agitation.

While the recession in the 1880s accelerated violence and expulsion attempts against the Chinese, dire economic circumstances cannot be solely blamed for this violence. Normal people do not try to forcibly remove an entire population because you perceive them as doing better. The attempts to expunge the Chinese from Seattle were fueled by racist ideals about who belongs in America and who does not. This look into the past reveals the resilience and perseverance of Chinese Americans that have continued to exist in Seattle.

About the writer: Tý Deitz is a mixed South Vietnamese American studying American Ethnic Studies and English at the University of Washington.

Donate

Acknowledgements