Three Chinatowns

Seattle’s First Chinatown

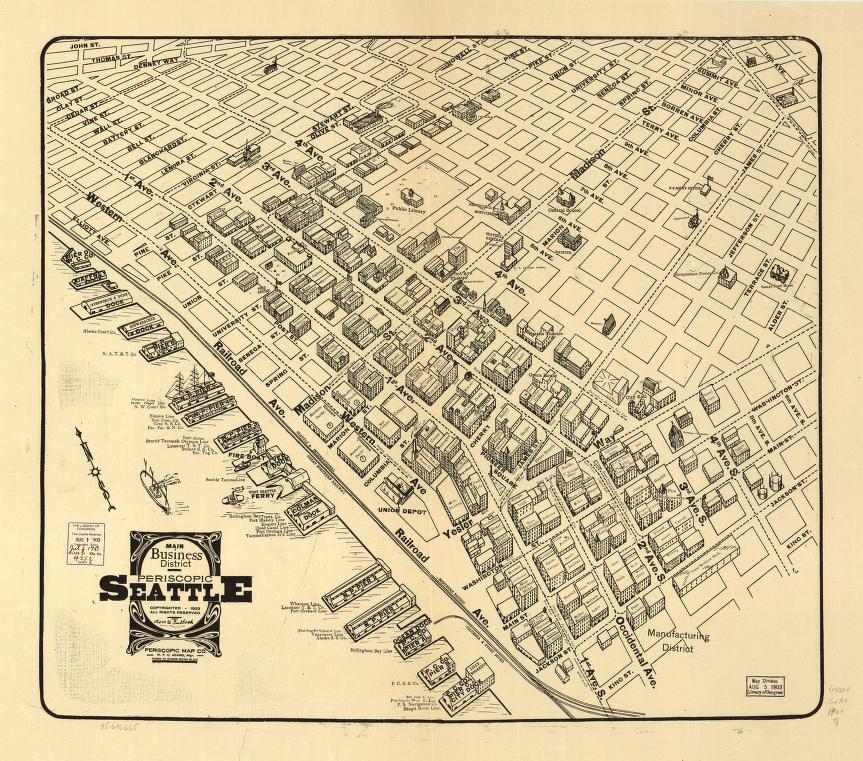

In 1860, there was one Chinese individual documented in the Washington Territory census, most likely sixteen-year-old Chin Chun Hock. Chin started as a domestic worker, arriving only nine years after the first White settler, Arthur Denny. Another Chinese migrant, Chen Cheong, opened the area’s first Chinese-owned business in 1867 selling cigars on Commercial Street (now Occidental Avenue). The following year, Chin Chun Hock created the Wa Chong Company, a general merchandise store near the tideflats south of Henry Yesler’s lumber mill and at the bottom of Mill Street (now Yesler Way). Starting in 1870, the introduction of railroads caused a significant expansion of population and industry. The urgent demand for laborers to build these railroads prompted a transcontinental movement to employ overseas workers, hundreds enlisted from China. The population in Seattle had reached 3,400 by 1876, with 250 of them being Chinese and an added 300 transient Chinese laborers. These men worked an array of jobs – as merchants on the waterfront, at canneries along the Puget Sound, hop farms and coal mines in present-day King County, and some in the lumber mills of Kitsap County. As the amount of Chinese migrants multiplied, the waterfront area developed into a Chinatown – a growing center of residential and business establishments.

The Second Chinatown

Needing to expand, Chinese residents and businesses gradually advanced away from the waterfront to Washington Street, between Second and Third Avenue in current day Pioneer Square. The move was largely influenced by Chin Chun Hock when he relocated the prominent Wa Chong Company to Third and Washington Street. The Wa Chong Company sold various imported goods from China including general merchandise, tea, herbs, furniture, and clothing. It was also a place for Chinese Americans to congregate, build community, as well as find contracted work, food, and shelter.

There was a major economic decline in the 1880s and animosity from white settlers toward Chinese laborers s

urged as they were accused of stealing jobs. There were already anti-Chinese sentiments and policies in effect, such as a measure in 1853 denying the Chinese the ability to vote, and again in the mid-1860s with laws including “An Act to Protect Free White Labor Against Competition with Chinese Coolie Labor and to Discourage the Immigration of Chinese,” as well as a tax for each Chinese resident in the territory. Soon, there were numerous instances of violence toward the Chinese – injuring, killing, and driving them out of their towns. On February 7, 1886, a large group of white residents attacked 350 Chinese people in an effort to force them into leaving the city by boat. Two hundred of them departed on a boat the following morning. The next week, another steamer landed and an additional 110 Chinese people departed, and the rest were planned to be taken by the next steamer. By the following week, there were only a few Chinese merchants and domestic servants left in Seattle.

The economic conditions increased and just two years later, 300 Chinese people populated Seattle, the city they had recently been involuntarily removed from. In the Great Seattle Fire of 1889, the central business districts in the city had burned down, including the majority of Chinatown. After the fire, Chinese workers were essential in the effort to rebuild Seattle; they constructed buildings, paved streets, and helped establish the Northern Pacific Railroad. Chin Gee Hee, an affluent merchant, labor contractor, and former partner of the Wa Chong Company, opened the Quong Tuck Company on Second Avenue and Washington Street – one of the first brick buildings created after the fire. Second Avenue and Washington Street consisted of three Chinese restaurants, a grocery store, eight laundries, and four general merchandise stores. The now 400 Chinese people who lived in Seattle resided in small spaces above the businesses on Washington Street, between Second and Fifth Avenue.

The Chinatown-International District

The Chinatown-International District (C-ID) in Seattle is uniquely diverse in that it is the only neighborhood in the continental United States where Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos, African Americans, and Vietnamese people unified together to form a multicultural community.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the Washington Street area Chinatown was starting to get congested. In 1900, 434 Chinese people were counted in Seattle, and by 1910 there were 924. After the Jackson Street Regrade Project, a Chinese investment group overseen by Goon Dip constructed buildings on the south side of King Street, from Eighth Avenue to Maynard Avenue, including both Kong Yick buildings. Other businesses and residents began moving to the King Street area from 1910 to 1920, where the Chinatown-International District (C-ID) is today. The ultimate dissolution of the old Chinatown was the Second Avenue Extension in 1928. The city decided to pave a passage from Second Avenue between Stewart Street and Yesler Way to the Union railway station on Jackson Street, uprooting the center of old Chinatown. After the mid-1920s just a few Chinese businesses and residents were left, and by World War II each Chinese establishment had closed. Chinatown around King Street was acknowledged as the primary Chinese community in Seattle in the early 1930s.

North and east of the new Chinatown, by Main Street, Japanese immigrants established a Japantown, or Nihonmachi. The lively community of Japantown, its many businesses, communal spaces, and homes, were evicted when Japanese residents were incarcerated in World War II. Filipino laborers who arrived in the city during the 1920s and 1930s started to move to the district, setting up shops, restaurants, and clubs near Maynard Avenue and King Street – which people liked to call “Manilatown.” Black businessmen operated jazz clubs on Jackson Street, where prolific musicians would play and socialize. Later, in the 1960s, immigrant groups from Korea and the Pacific Islands also found home in the Chinatown-International District. From the 1970s to 1980s there was a wave of refugees from Southeast Asia, including Vietnamese, Laotian, Hmong, and Cambodian families who congregated in the 12th Avenue and Jackson Street location, now known as Little Saigon.

The Chinatown-International District endured harsh transitions during the 1950s to 1970s, predominantly due to the construction of the I-5 highway in the 1960s. The interstate cut right through numerous communities, demolishing or displacing local businesses and homes. The building of the Kingdome also threatened the neighborhood and incited protests throughout the community in the early 1970s. Despite the difficulties the C-ID has faced and continues to encounter, it still stands strong as a communal hub and cultural cornerstone for many.

Today, the C-ID is full of places to eat, shop, and explore with admiration for the area’s deep cultural history. It is one of the city’s eight Historic Districts, a status enacted in 1973 by the City of Seattle to maintain and nurture the dynamic Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander communities. With roots from Chinese immigrants settling at the waterfront, expansion up Washington Street, then the shift to King Street and contributions from diverse ethnic groups, the Chinatown-International District remains alive with many stories to tell.

Kay Wong

Bibliography

Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest. “Timeline: Asian Americans in Washington State History.” Accessed March 20, 2024. washington.edu/uwired/outreach/cspn/Website/Classroom%20Materials/Curriculum%20Packets/Asian%20Americans/Section%20IV.html

Chew, Ron and Cassie Chinn. Reflections of Seattle’s Chinese Americans: The First 100 Years. Seattle: Wing Luke Museum, 2003.

Chin, Doug. “The First Chinese in Seattle,” International Examiner, December 16, 1981.

Chin, Doug. “The Rise and Fall of Old Chinatown,” International Examiner, September, 1976.

Chin, Douglas and Arthur Chin, The Settlement and Diffusion of the Chinese Community in Seattle, Washington, 1973.

Crowley, Walt. “Seattle Neighborhoods: Chinatown-International District- Thumbnail,” HistoryLink.Org, May 3, 1999, accessed March 20, 2024, https://www.historylink.org/file/1058.

Faltys-Burr, Kaegan. “Jazz on Jackson Street: The Birth of a Multiracial Musical Community in Seattle.” HSTAA 353, University of Washington, Fall 2009.

Jue, Willard G. “Chin Gee-Hee, Chinese Pioneer Entrepreneur in Seattle and Toishan." Annals of the Chinese Historical Society of the Pacific Northwest, 1983: 31-38.

Jung, Moon-Ho. "Outlawing "Coolies": Race, Nation, and Empire in the Age of Emancipation." American Quarterly 57, no. 3 (September 2005): 677-701. https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2005.0047.

National Parks Service. “Seattle Chinatown Historic District (U.S. National Park Service).” Accessed March 20, 2024. Nps.gov/places/seattle-chinatown-historic-district.htm.

Seattle.gov. “International Special Review District.” accessed March 20, 2024. Seattle.gov/neighborhoods/historic-preservation/historic-districts/international-special-review-district.

Tsutakawa, Mayumi. “How The Kingdome Spurred The Asian-American Community's Coming Of Age,” The Seattle Times, July 8, 1999.

Wing Luke Museum. “Chinatown-International District.” Accessed March 12, 2024. wingluke.org/cid.

Donate

Acknowledgements